- Home

- Janice Y. K. Lee

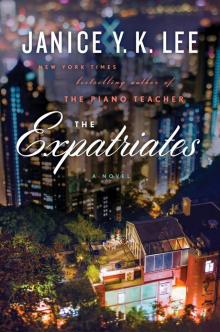

The Expatriates Page 6

The Expatriates Read online

Page 6

The first few months after giving birth, Margaret felt nauseated, as if she were still pregnant. Her breasts, big and alternately baggy or rock hard, leaky and messy. The soft, shifting flesh of her belly—she was not one of those women who sprang instantly back into prepregnancy fitness—being squished into her jeans and marked with angry red splotches where the buttons pressed. Her hair was incredibly greasy, and then it all fell out. She sweat and sweat.

And the baby! Daisy was not a hard baby, but not easy either. All those terrible women she met who expressed pure happiness in their new roles and ignorance of anything as awful as bleeding nipples, or hormonal fluctuations that left you homicidal. The most they would admit to was a slight nod to the fact that it might be a little hard, not sleeping for three months, becoming a new, completely different person, the sheer relentlessness of it, that you would never be able to change back, but then they always follow it immediately with a “It’s so worth it, though, isn’t it? I don’t even think about it when I look at Sadie’s adorable face.”

Margaret, who was used to being above average in most things, couldn’t understand the gap. This was the hardest thing she had ever done, and arguably the most important. And no one was acknowledging that it really, really sucked. A lot.

This metamorphosis into that other being, that mother, was excruciating. She noticed that it got better in quarters. Three months, six months, nine months. And then suddenly she woke up and she felt better. She was not back to normal—that baseline had shifted. But she could cope with her life.

Later, people would ask, “Why didn’t you see anyone?” And certainly, after the incident happened, she did—it was practically court-ordered. But at that time, with that first child, she never felt that desperation was a good reason to see someone. And where would she have found the time? She didn’t have time to shower, let alone see a therapist or have a leisurely cup of coffee with a friend. And then the others came, and they were different and easier, because she had already crossed over into that other country of motherhood.

She thinks about that a lot, how you get used to everything, that the first shift is difficult and horrible, and you live your life because what else can you do, and then one day you wake up and your life seems normal. You start to forget the bad times. You shift into your new self.

At least, that’s what she had thought about life and change.

The other pregnancies were less vivid, and she was certainly less careful. She drank coffee with Philip; in the last five weeks of her pregnancy with G, she had a glass of wine every few nights. Of course, there was not the luxury of movie watching and solitude. She had Daisy and then Philip and her whole blazing new life as a mother. Everything revolved around the children. And here she was, in Korea, traveling with them to her quarter home country and feeling blessed.

They spent a lovely day wandering the streets of Insa-dong, where they bought colorful stationery, browsed through secondhand bookstores, walked through art galleries and craft shops, and saw a cart vendor selling fried silkworms from a cast-iron vat—a nostalgic treat for those who remembered when Korea was so poor they couldn’t afford meat and insects were an important source of protein. They couldn’t bring themselves to try them but bought roasted chestnuts from the vendor next to him, cracking and peeling the soft shells and eating the warm meat of the nut. Margaret carried G when he got tired, and he nestled his head into her neck.

At three, Margaret shepherded the exhausted kids back to the hotel and found Mercy doing yoga on a towel on the floor. “Did you have a good day?” she asked.

“I just walked around here,” Mercy said, from down dog. “I’m going to try to meet up with some relatives if I get a chance.”

“Great.” She paused. “Well, the kids are hungry, since we’re an hour ahead. You might as well eat now. I guess you could order room service, or go down to the restaurant? What do you think?”

“It’s pretty small in here,” said Mercy. “I think we should probably go downstairs.”

“Okay, just don’t leave the hotel.” She felt absurd that she even had to say it but wanted to be sure. The kids were excited to see Mercy, and she took them, chattering, telling her all that they had done, down the hallway and into the elevator.

Margaret went back to her room and got into the shower. She was meeting Clarke in the lobby at five, and they were going to the company headquarters to meet some people and then out to dinner.

In the car, Clarke ruffled her hair and asked about her day.

“It was good,” she said. “Where we were was really charming. And I think we’re going to meet my great-uncle tomorrow. He had his son e-mail me back with a time and a restaurant. Very sweet e-mail. We’re going to have lunch.”

“Great,” he said. “I don’t think I can make it. Is that okay?”

They sat for a moment, quiet, happy, hands intertwined in the backseat. She remembered this moment later as one of the last times she felt totally content.

At the office, she met some people, who all bowed, so she bowed back, feeling her 75 percent Americanness very strongly, and when she went to the bathroom, she saw a strange glass cabinet full of toothbrushes.

“What’s that for?” she asked one of the ladies in the office.

“Koreans like to eat Korean food,” the woman replied, giggling and covering her mouth, “but it smell very strong. We always brush teeth after lunch. It is an ultraviolet light cleanser, so it sterilizes all the toothbrushes so it is hygienic.”

“Oh, wow,” Margaret said. She was six inches taller than any other woman in the room and felt incredibly large.

They went out to a barbecue restaurant and ate bulgogi and drank beer and came back to the hotel with smoky hair and pungent clothes, and when she peeked into the kids’ room, they were watching a movie, bathed and pj’d, and they swore they had brushed and flossed. Mercy winked at Margaret, and she softened. She was charming, in an odd sort of way. She felt sorry for Mercy, although she didn’t know why.

The next day, she met her extended family for lunch with the kids, having given Mercy the day off again. It was at a barbecue restaurant (the amount of meat you consumed in Korea was extraordinary) with an outdoor garden and ponds, and they all took a photograph in front of the fake waterfall. It reminded her of old-fashioned family portraits as they seated her great-uncle and his wife in the front center and radiated out, agewise. There was much exclaiming and smiling and broken English and broken Korean. They were about twenty in all, many second and third cousins, who had brought their children, who played with Daisy and Philip and G in the outdoor garden. Margaret showed them pictures of her father and his parents, and they showed her old photo albums of their side of the family. The relatives showered them with presents—a woman’s silk scarf for her, hair accessories for Daisy, a tie for Clarke and toys for the boys—and she was mortified that she hadn’t thought to bring anything. She snuck off to pay the bill, and when the waiter presented her with the credit card slip, there were stricken faces all around.

“I have to pay!” she said. “So many presents! I no give anything!” resorting to pidgin English for some embarrassing reason.

“You our guest,” they said. “You come to our country.”

She signed the slip, embarrassed, and finally they smiled.

She looked at a cousin and tried to see her father’s face. He had died too early, her father, and she could not remember much about the way he looked anymore. She wanted to feel a connection to this family of hers but knew that if she saw some of them in the hotel lobby the next day, she would be hard-pressed to recognize them.

At the end of the meal, she brought the kids back to the hotel for a rest before dinner. Mercy was there, and she ordered another movie for them.

“We’ll go somewhere fun for dinner,” she said. “Daddy has to go to a work dinner, so it’ll be you guys, me, and Mercy.”

And then. And then.

She went to pick them up a few hours later, and she and Mercy took them out to the bustling Myungdong area, just in front of their hotel. It was crowded and neon and loud and had a carnival atmosphere, with people selling remote-control cars and light sticks out of boxes, cart vendors lining the sides of the road, shoe and clothing stores blaring K-pop. The young kids had dyed hair and wore trendy clothes.

“Korea is so consumerist,” Margaret had said to Mercy. She remembers this so clearly, the unimportant remark.

“I know,” Mercy said. “It’s terrible.”

Margaret was watching all three kids, and then one kid, and two kids, all at the same time, and assumed Mercy was doing the same. They were darting back and forth, looking at this display, shouting to one another about that store window. They came upon a soft-serve ice cream cart where the ice cream was dispensed in swirls ten inches high.

Margaret bought everyone a cone, and they sat down and licked them clean. Margaret went to the bathroom inside a Starbucks and came back.

“Where’s G?” she asked.

Mercy looked around slowly. “He was just here,” she said.

They both looked around, couldn’t see him, asked Daisy and Philip if they knew where he was. They didn’t.

Margaret started walking around, looking for him. Then she started calling his name. Then, after a few minutes, there was that moment when it tipped into panic and she started shouting his name, not caring if she was making a spectacle of herself. She started screaming at the top of her lungs. “G! G! Where are you?”

The amazing thing was that life went on. Around her, people waited in a line to get movie tickets. A girl in a doorway lit a cigarette. But they were all staring at her, staring at the crazed, shouting woman. They were living their normal, regular life, only they were all staring at her, wondering what was wrong. Suddenly they all seemed sinister to Margaret, as if they were all possible child abductors, or insanely important, as possible witnesses with clues as to where G was: That old man with the salt-and-pepper beard was a pedophile, that young man with the slicked-back hair and the black leather jacket was a cog in a child-smuggling ring, that nice-looking woman must have seen something. But no one came forward, no one bolted. There was no G. It was as if she were in one of those movies where the camera swings around 360 degrees, dizzyingly, relentlessly. She stood and she ran and she turned around and scanned and screamed and screamed.

It was the lack of an answer, his small voice crying, “Mama!” as he came running toward her. The same voice that had once, already it seemed so long ago, triggered irritation in her, irritation that she was to be interrupted in the middle of something, that his knee had been scraped and he wanted a bandage, or that his brother wouldn’t share, and she would have to get off the phone, or stop writing down her grocery list. His voice was gone.

Later the technology defeated her. Her phone didn’t work. She had just gotten the newest phone, and there was some type of new network it was supposed to work on, and it just didn’t. As soon as they had arrived in Seoul, her phone had started acting erratically. She hadn’t been getting e-mails, only sometimes texts would go through; the phone would ring randomly and never connect. The idea that something so prosaic could ruin her efforts to find her child made her even crazier. She crouched down on the street, pushing at different buttons, trying to get it to work, trying to borrow a phone from someone else, although she didn’t even know the number for the police. Shouting about 4G networks, police, and G, as if they were all important. She was trying to get something to go right, even just a phone call. She was trying to remember how to dial in a foreign country. She needed to get in touch with Clarke. She needed to know if abduction was common in Seoul. She needed so many things. She remembered later that her phone sometimes rang, but when she picked it up, it disconnected, and later, that it was on vibrate, because she must have pushed that button inadvertently. She had her phone in her shaking hands, clutching it with desperation, willing it to connect her to someone who could help, someone who would do something. She screamed at Mercy to go to the hotel and get someone to help. Around her, Korean people stopped and stared. She noticed this too, in a corner of her mind, that they just stood still and stared at her. She supposed they were voyeurs, but also grateful that today it wasn’t them, that disaster could press by you so closely in a crowd that you could feel its terrible presence but that you could go home and eat dinner with your family and say a silent thank-you that it had passed you by.

Daisy and Philip were mute, standing close to her without being told, terror holding them rigid. She regretted this later, that they had seen her so unhinged. She thought that Clarke would have handled it better. They didn’t cry until much, much later, when they were told to go to bed by their ashen father, and then they cried and cried and cried and couldn’t sleep until all of them went silent in the room, Margaret holding Clarke’s hand as they sat in chairs overlooking the street where it had all happened. She had spent a few hours in the nearest police station filling out forms with a nice young lady who spoke some English. The added layer of not knowing how to speak or write the language she saw all around her made her feel as if she couldn’t breathe, that she couldn’t move freely in this world.

She had wanted to stay in the street where she had last seen him, but after five hours, at eleven at night, the other children were falling apart and needed to be in a quiet room. Still, she had put them in their room with Clarke, Mercy a black void among them, not physically there but a terrible presence still, and then she had gone back to the street, where she had stayed until one in the morning, when the streets were empty and she had to admit there was little chance that G would be brought back. She came back and watched Daisy and Philip shift uneasily in their restless sleep, with this blackness inside her stomach. They were still in their clothes. She had no idea where Mercy was.

This is what could kill you about children as you watched them: the way they slept, their open-mouthed unconscious faces, their frail collarbones, their defiant stance right before they cried, their innocence. Their crazy, heartbreaking innocence. It could really kill you, if you thought about it.

She wanted the hours back. She wanted to go back ten hours, to when life was understandable. She wanted to not ever have to go to the bathroom again. She wanted to have a kind stranger lead a crying G back to her, to be enfolded tight in her waiting arms, to be squeezed, to feel the corporeal flesh of him, the shaking, sobbing child. This was understandable. The absence of him was incomprehensible. Most of all, she wanted to erase Mercy from her life. To absent the girl and get her boy back. That was what she wanted.

Part II

Hilary

HILARY PAUSES. There is a stain on the piano’s ebony surface.

“Puri,” she calls. “There is a water mark here from where Julian left his glass during his lesson.”

At some point in her life, she realized that she never says anything directly anymore. She has become a master of indirection, or misdirection. She will say, “Mr. Starr is arriving from Kuala Lumpur at 11:00 p.m. tonight” or “I stained this blouse with red wine at dinner,” when she should say, “Please keep the lights on and notify the gate guard that Mr. Starr will be late” or “Send this out for dry cleaning.”

Puri, of course, cannot always decode the message, and Hilary will come across the garment, still stained, folded neatly in her closet, or David will complain that the guard didn’t let his airport car into the complex without an ID check.

She has noticed how, as she grows older, she is more and more reluctant to say anything directly, even to her husband.

She will tell him, “I haven’t told anyone else about that,” when she means to say, “Don’t tell anyone.” When David later says he has mentioned it to a friend, she gets upset, and he will exclaim, in the simple way of men, “Why didn’t you just tell me you wanted to keep it private?” and she will

retire, injured. He should have intimated, she thinks. Intimated, because they are supposed to be intimate. He should have known.

So she does not say, “Please try to get the stain off the piano.” She walks into the kitchen and says, “Puri, I’m leaving now.”

Julian is sitting there, having a snack. Usually she would be there with him, but she forgot her lunch appointment and now cannot cancel. He is seven, wary. He comes, once a week, for his piano lesson, paid for by the Starrs, a new arrangement that has already revealed itself to be static and in need of change, but one that she has no idea how to alter. She sat with him during his lesson, as she always does, watching his slender fingers hover over the keys. He is talented. She found Julian in foster care, half Indian, half Chinese, left by his teenage mother. At the table now, he looks up and gives a shy smile, with his light brown skin and beautiful dark eyes, ringed with impossibly long lashes. How odd, she thinks, to not know whether his mother was the Chinese or the Indian half. The system must know, she thinks, but she doesn’t want to ask. But this seems a vital part of the equation. He will want to know, she thinks, and he should be able to find out. She should find out for him.

“I have to go out for lunch, Julian. Sorry I couldn’t reschedule it. Sam will come to take you back in fifteen minutes, after he drops me off. I’ll see you next week.”

She thinks he understands her but isn’t sure. His English is almost nonexistent, but he is agreeable. He gets in the car to come here, he plays the piano, he eats the snack they give him, and then she takes him back to the group home. She gives him a kiss on the cheek and goes home. Another odd event in his odd life.

The Expatriates

The Expatriates The Piano Teacher

The Piano Teacher